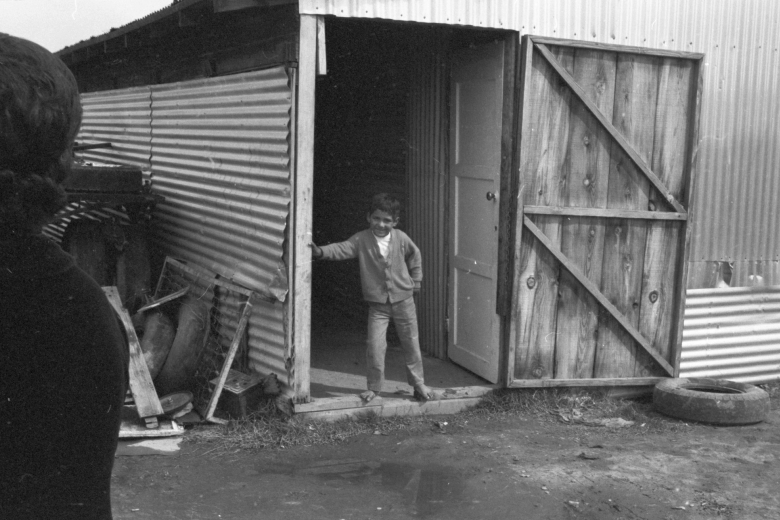

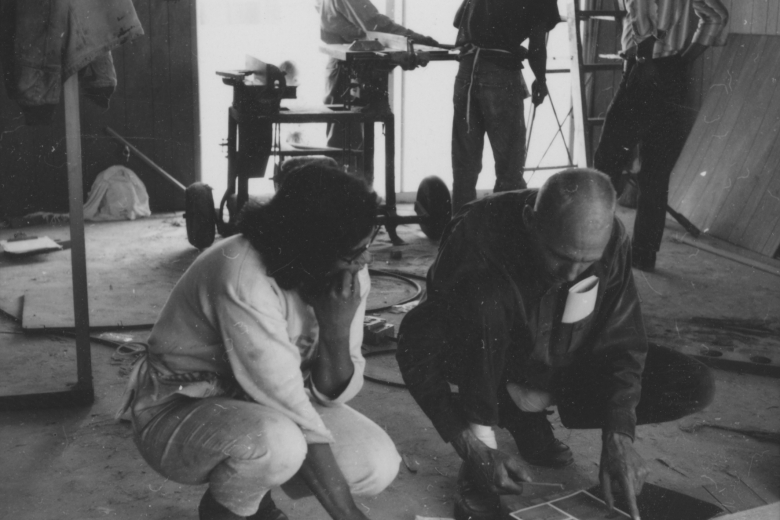

In the 1950s, AFSC began to work with migrant farmworkers fighting for basic services such as access to water, and elimination of tin-shack public housing. This work expanded into Proyecto Campesino in Visalia, California, a program that provided direct services to farmworkers and helped them advocate more effectively for themselves when interacting with powerful growers and legislators.

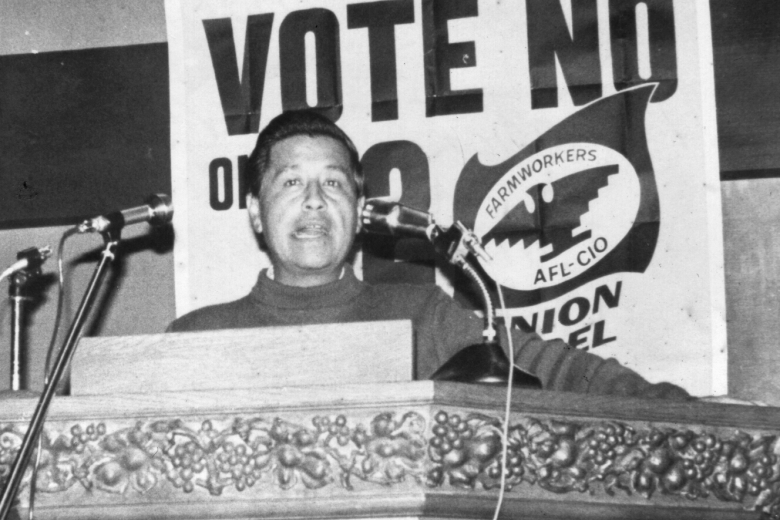

Later, our staff supported the struggle to establish the United Farm Workers, providing meeting places, collecting funds for strikers, and paying the salary of the union’s chief negotiator. In 1975, Cesar Chavez acknowledged how essential AFSC’s support had been to the UFW. In turn, we acknowledged the great value of participating in the union’s “practical demonstration of a nonviolent movement.”

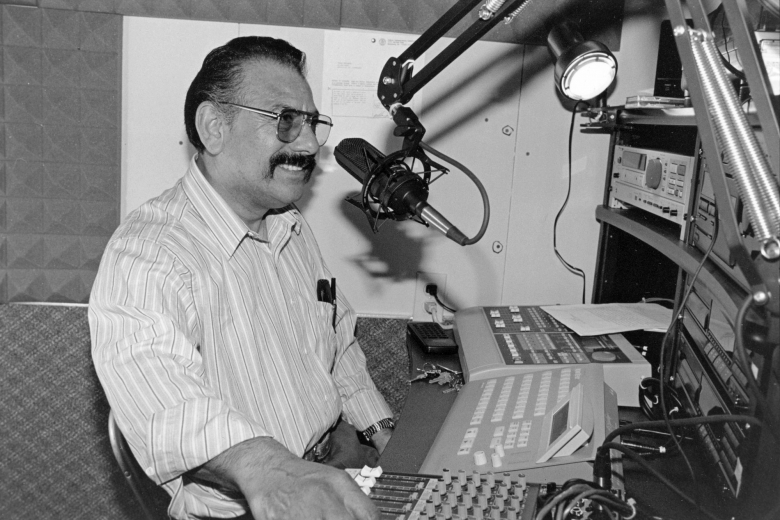

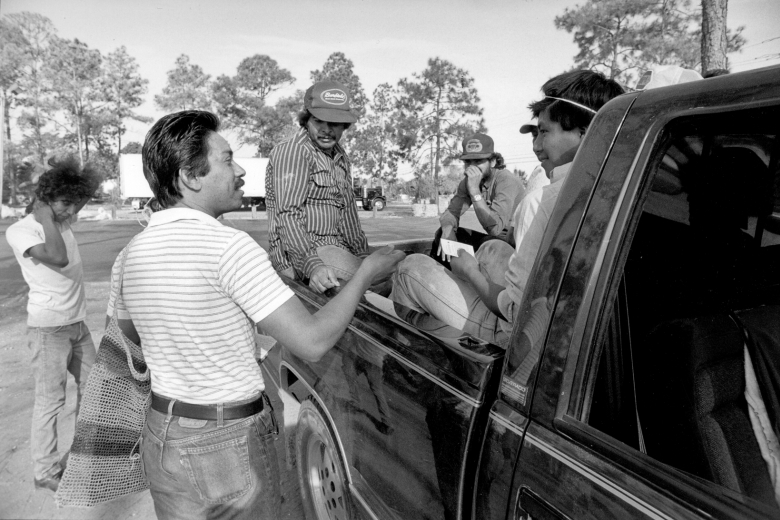

When the Immigration Reform and Control Act created an opening for permanent residency in the 1980s, we helped thousands of farmworkers and their families apply. Our longstanding Spanish-language radio program, Radio Grito, amplified workers’ voices, and connected them to resources and to each other. AFSC programs in the Pacific Northwest and South Florida have also supported migrant families engaged in agricultural work.