It was a hot summer day in 1966. Bonnie Kay and I were heading to Pageland, South Carolina where, as AFSC volunteers, we would spend the summer preparing local black children to desegregate the public schools.

We passed a large billboard welcoming us to South Carolina in the name of Governor Robert C. McNair. I felt I had passed the point of no return. Bonnie and I were White volunteers, on our first trip South. We had been assured by AFSC that resistance to integration had not been as violent as in Mississippi and Alabama, but, I thought, “Still, this is the South.”

Bonnie was a former Peace Corps volunteer from Ohio, and I was a 28-year-old California lawyer. We had been trained by AFSC staff in High Point, NC and we were to tutor the first generation of black students to attend the previously white schools. We were spread out, in twos, to four towns and only met as a whole program group twice during the six-week project.

We wound our way over dirt roads and drew up in front of a wooden shack where, we were told, the woman who arranged for this project lived. She would take us on to our host families. Only she didn’t. We sat on the sandy front yard for about 4 hours. Finally, an old beat up car pulled up, and out strolled a tall thin Black man wearing concrete stained working clothes. He greeted us warmly and took us to his house, where I would stay and next door to his sister’s house where Bonnie would be housed.

I learned later the reason for the delay. They had assumed we would be black. Our potential hosts were not up to hosting white folk, leaving the Rev JD Manus to sort out when he returned from his job. This was my first introduction to the man who would be a significant part of my life.

JD, as McManus preferred to be called, had organized a community meeting to introduce our tutoring program. We were skeptical as to whether anyone would show up. However, they did and filled the church. This became a pattern. If J.D. said something will happen, you could count on it taking place, and JD would be leading it.

At that meeting we discovered that we would have 35 students, representing grades 2 – 12. So much for the main thrust of our training – tutoring on an individual basis. We had to invent a Freedom School on the spot. We had the older kids in for morning classes that Bonnie and I ran. In the afternoon the older kids stayed on and tutored the younger ones. Bonnie and I were always available to them. Amazingly this worked. Academically the children improved significantly, thereby erasing some of the shortcomings of the separate but unequal “colored” school. They developed positive ties with whites.

One of the highlights was a field trip for the older youths. The Charlotte Friends Meeting opened their homes to the group, where they spent the night. A summer theatre production of West Side Story gave them a musical experience and a different perspective on race relations. Sunday morning they went to Friends Meeting, where they led a discussion about racism and civil rights and about their own experiences.

This glimpse into a world where they were accepted for whom they were was key to expanding these students’ horizons. At the very beginning of the summer, we had asked the 11th and 12th graders what occupation or job they would like to do when they graduate. Answers were traditional Black employment roles: school teachers, social work, beautician. Ten years later I called Delta Airlines to buy a ticket. The ticketing agent recognized my name and told me that she was one of that group of 11th and 12th graders Others students went on to become a lawyer, a doctor, factory administrator, a book keeper, and a school board member.

Meanwhile, each free evening JD and I would talk long into the night. We covered a broad range of subjects such as his travels throughout the United States, and the years of preparation for school integration that he had worked on. We explored the theory of non-violence and non-violent action. While I was committed to non-violence, it was comforting to know that JD slept with a loaded shotgun under his bed.

I gave him advice on how to deal with government agencies, and, of course, we talked politics. This informal dialogue, turned out to be a mutual mentoring experience that went on in various forms until JD’s death in 1997

After the AFSC program was finished, I got a job with the Georgia Council on Human Relations to promote understanding of rights to welfare support, and to provide resources to local bi-racial chapters. The Council had an excellent collection of “how to” pamphlets on how to combat segregation and related issues. I sent these to JD every few weeks. But he didn’t seem to use these resources.

About a year after the AFSC summer program closed, JD told me that he had a cancerous growth behind his ear. I suggested if he would come to Atlanta I would arrange for second opinion from a recognized cancer specialist. Although fearful he agreed, and I drove him to Atlanta. All the way he talked about how violent the resistance had been in Georgia and how little violence had been experienced in South Carolina. “Why, in Pageland when I see a doctor I never use the colored waiting room. I sit in the white one.” Pageland was still thoroughly segregated.

In Atlanta that day we went to the doctor’s office where a white nurse greeted “Mr. McManus” warmly and sent him to the waiting room. He looked doubtful and asked me where the colored one is. "This is the only one," I replied.

Later we drove around the countryside with JD at every stop going to the bathroom to see if it was segregated. They were not. Nor were the motels we stayed at. Of course I had done my homework and limited our agenda to counties that are more progressive. Shaken out of his complacency, he went back home and within six months of the Atlanta trip, he had used the tools I had sent him, and his own resources, to eliminate segregation in Pageland. White and colored signs were now history. He then made a major step ahead by taking on economic issues – wages, job discrimination, mortgage discrimination, red lining, job training and placement, and more. Often he was using my “how tos” to guide him.

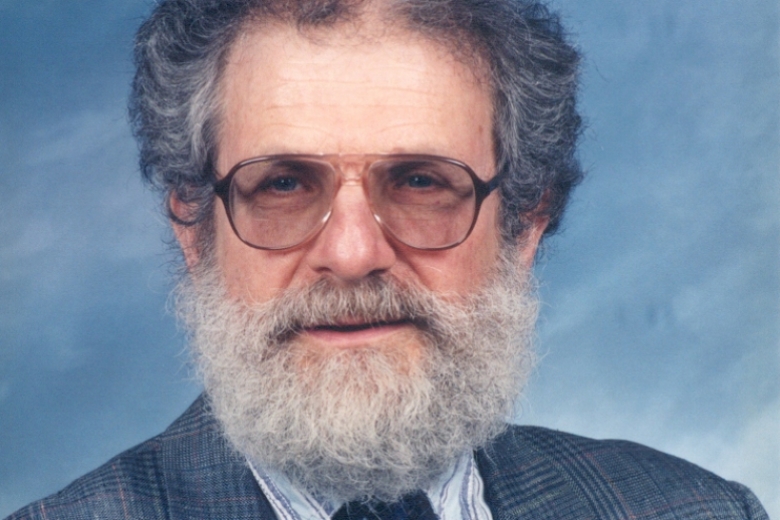

JD eventually was elected to the county school board and to the Pageland City Council, and we continued our sporadic dialogue for over 30 years. It was a privilege for me to know this amazing man, and in the 1980s I made many trips to Pageland to interview him for an autobiographical book, Rev. James D. McManus – The Civil Rights Years.

FOOTNOTE

Rev. James D. McManus – The Civil Rights Years is available from Paul Wahrhaftig, 5806 Black St., Pittsburgh PA 15206 for $10.00.