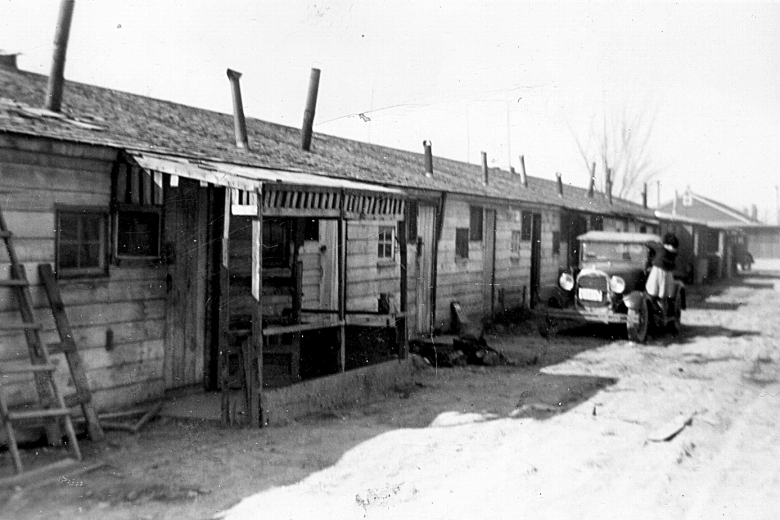

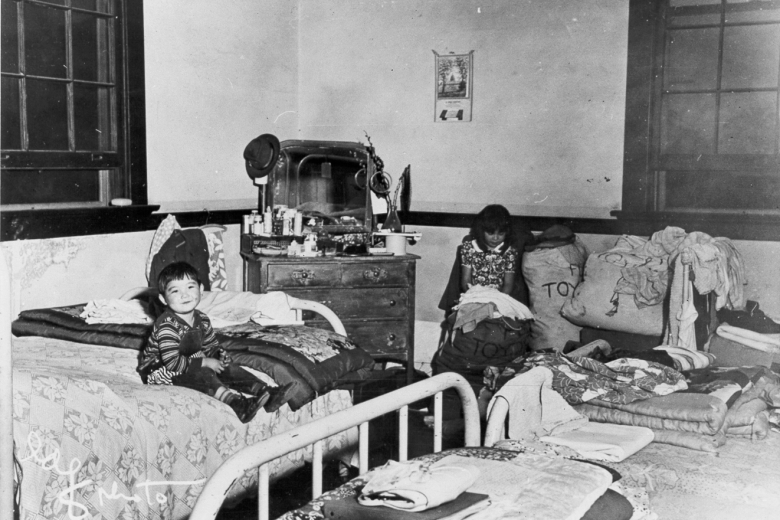

Shortly after the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, the U.S. government forcibly relocated more than 100,000 people of Japanese heritage from their homes along the West Coast. They were sent to internment camps to live in dirt-floor huts without privacy, adequate food, or healthcare.

Clarence Pickett, then executive secretary of AFSC, declared this a “calamity” and staff began visiting almost immediately. Some AFSC personnel lived in the camps alongside the shocked, displaced residents. This provided not only material aid, but also the assurance that people outside the camps were concerned about this enormous human rights violation.

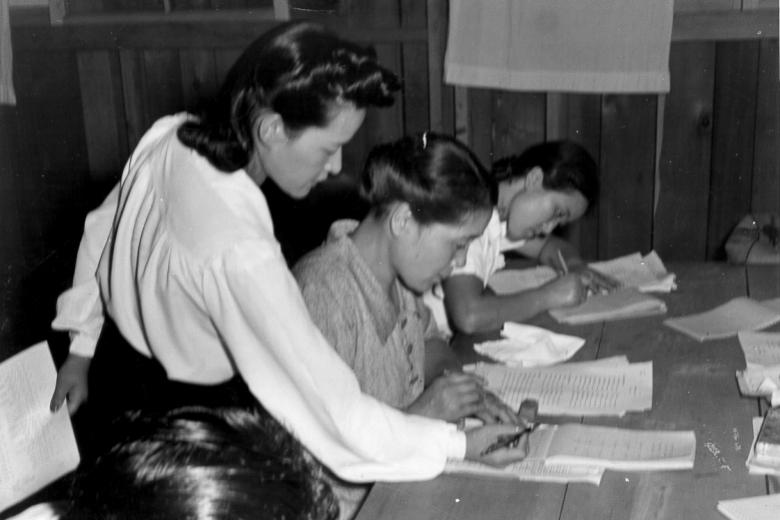

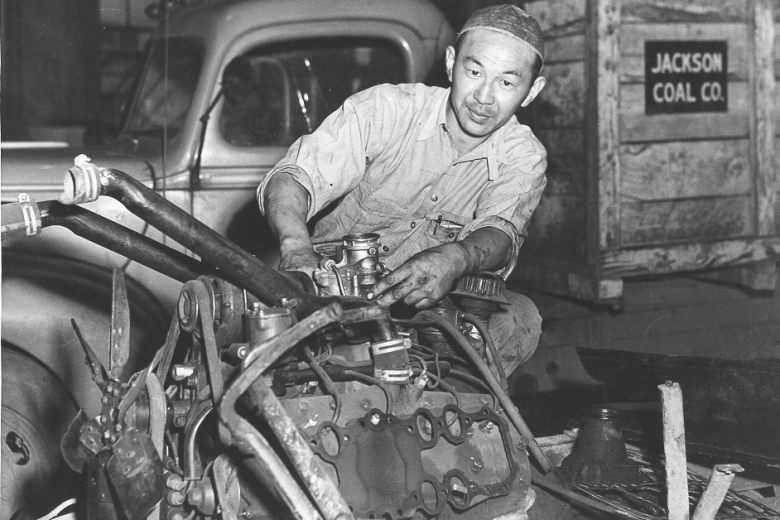

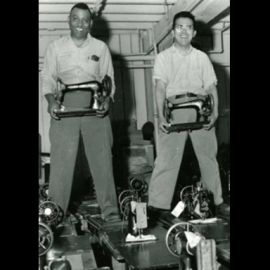

AFSC used two strategies to help achieve the release of residents from these camps. First, they identified colleges and universities in the Midwest and East who would accept qualified students. Second, they found jobs and housing for working-age men who were then able to bring their families to live with them.

It took support from many open-hearted Americans to educate, house, and employ fellow citizens who were being labeled as “enemies.” Ultimately, this effort helped secure the release of over 4,000 people.