My first trip to Concord, twenty years ago this month, changed my life.

I arrived on a Monday morning with a group of near-strangers in the back of a National Guard truck. We were among the 1415 arrested the previous day at a nonviolent occupation of the Seabrook nuclear construction site. For the next two weeks, the Concord National Guard Armory would be my home.

My truckmates were a diverse lot, made up of fragments of several “affinity groups,” or mutual support groups of ten to twenty people formed for the demonstration.

I was closer to the stereotype of a Clamshell Alliance member: a 22-year old, long-haired college student, passionate about the “No Nukes” cause, committed to nonviolent protest, and proud to get arrested for acting in accord with my beliefs.

The Concord Armory housed 276 of us. Other Clamshell arrestees, including all of the people with whom I had traveled to Seabrook, were dispersed among several other armories. The Monitor reported, “They look casual, the young people who demonstrated against the Seabrook nuclear power plant–but they’re completely regimented.” I would have preferred the word “disciplined,” for none of us were following orders.

Our discipline came from our shared commitment and training. Everyone who participated had to attend a training session, which gave everyone exposure to the principles and methods of nonviolence. It also provided familiarity with plans for the demonstration, a chance to think about the upcoming occupation and its likely consequences, and a time to form affinity groups and plan our trips to Seabrook. Knowing that everyone had shared the training experience and was committed to nonviolent protest enabled an unusual level of trust.

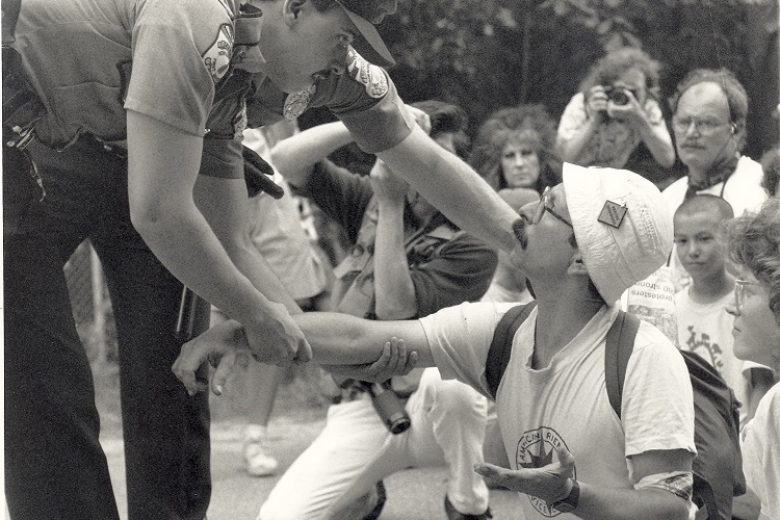

We were surprisingly good natured for a large group denied freedom and privacy, and for the most part sought to win over our captors to the anti-nuclear cause. “Prisoners and Guardsmen seemed to get along very well,” the Monitor reported.

Humorous incidents were frequent. Only family members were allowed to visit, and I was surprised when a guard told me my brother and sister had come to see me. Since I don’t have a brother, I assumed it was some college friends. I told the guard I had a very large family, and began guessing the names of all my friends until I came to Betsy, and the guard nodded. If I remember correctly, I never did guess my “brother” Joel, but the guard eventually smiled and let me see them both.

We were serious, too, especially about the conditions of our incarceration and the terms under which we would be released. In order to make sure we were treated equally, regardless of previous arrests or state of residence, most Clams refused to pay bail or accept release until everyone was released on their own recognizance (that is, with a promise to show up for court but without bail). We met in a large group to hear reports from lawyers, and in our affinity groups to decide what actions to take. Through a back-and-forth process between the small groups and representative assemblies (called “spokes meetings”), the entire body sought to reach decisions that everyone could accept. “It was like town meetings in which participants talk and talk and talk before deciding any final action,” the Monitor reported.

The twenty-year-old newspaper stories are revealing. An AP “news analysis” dismissed the direct significance of the occupation, saying “the true battle ground is before the regulators and not between police and demonstrators.” The same story quoted an anonymous lawyer who said “The demonstration may be stopping the next plant, but it may not have a direct effect on this one.” In fact, no reactors ordered since 1973 have gone into operation. The nation’s nuclear power industry is in a deep coma.

Manchester lawyer Bob Backus, who was probably the anonymous lawyer quoted above, addressed the Concord Chamber of Commerce mid-way through the second week of the incarceration. According to the Monitor, he said the price of the Seabrook nuke, then estimated at $2 billion, was “staggering.” A decade later, Public Service Company was driven into bankruptcy by the spiraling costs of financing Seabrook construction.

On May 13, two weeks after the occupation started, Clamshell lawyers reached an agreement with the state for the release of the 500 Clams who had not bailed out. Everyone would be marched through District Court where we would be found guilty without trial, automatically appeal to Superior Court, and released on personal recognizance. The terms were controversial for the Clams still in the armories, but in the end almost everyone accepted the deal. I stuffed a sock doll into a pouch on the front of my shirt, made a tail out of rope, put my hair into pigtails to simulate ears, and hopped into the courtroom to protest the “kangaroo court,” but I was relieved to be released.

When a reporter recently asked me about the personal impact of the occupation/armory experience, the best I could do was to quote Martin Luther King, Jr. “The nonviolent approach does not immediately change the heart of the oppressor,” King wrote in Stride Toward Freedom, the story of the Montgomery bus boycott. “It first does something to the hearts and souls of those committed to it. It gives then new self-respect; it calls up resources of strength and courage that they did not know they had.”

Participation in the Seabrook occupation twenty years ago gave me the experience King described, a realization of the power of nonviolence to transform those who use it, and transform a situation where it seems there is no alternative to the status quo. My life has never been the same.

*Abridged from The Concord Monitor