How was it that Courtney Siceloff and I found ourselves in the back room of a service station in Plains, Georgia, at a cluttered desk, typing our own permit for a vigil in a park catty-corner from President-elect Jimmy Carter’s home?

It began at the Disarmament Task Force meeting of the American Friends Service Committee’s Nationwide Peace Education Committee on a Friday before Thanksgiving in 1976. Jimmy Carter had just been elected president. In June, Carter had told the Democratic Party Platform Committee, “Exotic weapons which serve no real function do not contribute to the defense of this country. The B‐I is an example of a proposed system which should not be funded and would be wasteful of taxpayers’ dollars.”

The Stop the B-1 Bomber: National Peace Conversion Campaign had been the primary work of the AFSC’s Disarmament Program and our partners at Clergy and Laity Concerned (CALC) since the fall of 1973. Terry Provance, who was the Campaign’s co-director, along with Carol Ness of CALC, arrived at the Task Force meeting that November Friday morning with an idea for a Christmas Quaker Vigil for Peace in Plains, Georgia, supporting President Carter’s stand on the B-1 bomber. Terry rightly believed that the president-elect would come under pressure to back away from his position as he prepared to take office. The vigil would offer him a “friendly” reminder that people were counting him to stand strong.

Once the proposal was approved by the Disarmament Task Force, a suggestion was offered that the vigil could also become a way to reinforce Carter’s leanings toward reconciliation with Vietnam, a priority goal of AFSC’s Indochina Program. I was meeting with the Indochina Task Force that Friday morning in a third-floor conference room at the Friends’ Center on Cherry Street in Philadelphia. Terry climbed the stairs and shared his idea. As the peace secretary for the Southeastern Regional Office (SERO), I immediately realized that that our region would play a large role in the vigil’s implementation.

The Indochina Task Force saw the vigil as a way to lift up Carter’s better leanings toward healing the wounds of the Vietnam War. The issues that we wanted the vigil to present included: a meeting with the new president on February 11, when the Appeal for Reconciliation would be presented at the White House; dropping the U.S. veto of UN membership and the trade and finance restrictions imposed on Vietnam; repairing Vietnam’s infrastructure destroyed by the U.S. air war; and extending Carter’s promise to pardon draft resisters to include military resisters who deserted rather than fight in a war they believed to be wrong.

The proposal was approved that weekend by the Nationwide Peace Education Committee. In the two weeks that followed, it was affirmed by AFSC’s Board of Directors Executive Committee and the SERO Peace Education and Executive Committees. The date was set – Saturday, December 18 – quick decision-making for Quakers.

On December 8, a letter announcing the vigil signed by Courtney Siceloff of the Atlanta Friends Meeting, AFSC Executive Secretary Louis Schneider, and SERO Executive Secretary Wil Hartzler was sent to Jimmy Carter. It expressed our spirit of support and shared hope and asked for an opportunity to discuss with him our views on some issues he would face once he took office. A copy of the letter, along with an invitation asking for Friends meetings to encourage their members to participate in the vigil, was sent to meeting clerks across the Southeast.

The first week of December, Courtney and I were asked to visit Plains to find a location near the Carter home for the vigil, and to secure a permit from the authorities. We realized that the Secret Service was now in charge of security for the Carter family, and we thought its agents would demand a permit issued by the town of Plains.

It all seemed a little daunting to me as we drove down to Plains. I was 28 years old and had been a regional peace secretary for only a little over a year. I had recently filed a Freedom of Information Act request for my FBI file and discovered that I had been placed on a list of people for the Secret Service to watch around events involving the president. The listing probably originated with a Holy Week 1971 seminarians’ sit-in in the White House driveway that I participated in – at least that was the mug-shot that accompanied it. I was glad to have Courtney at my side.

Courtney was the director of the Atlanta Regional Office of the United States Commission on Civil Rights and had been the director of the Friends Frogmore Center in the late 1950s and early ’60s. The Southern Christian Leadership Conference used the Georgia sea island retreat center (originally a Friends school for enslaved people after emancipation) as a place to plan next steps, away from the day-to-day pressures of the civil rights movement. Surely, I thought, the authorities in Plains and even the Secret Service would respect Courtney and the intent of our vigil.

Without the aid of a GPS, Courtney and I found the Carter home on the edge of town and were surprised to discover a small, wooded public park catty-corner from it. How convenient. Our next task proved more difficult. Where was the Town Hall or the mayor’s office? We drove around the downtown streets of Plains – there weren’t many – searching for it. We found a small County Courthouse, but no Town Hall.

We stopped someone on the sidewalk and asked for the address of the Town Hall. With a smile, she directed us to a service station, evidently operated by Mayor A.L. Banton, who greeted us warmly. We told him we wanted to secure a permit to hold a vigil in the public park near the Carter’s home. He responded, “What’s a permit?”

I began to explain that it was a document that stated the terms of an agreement between a municipal government and a group requesting to use a public space for an event. He looked a little puzzled and said, “I don’t believe we have a form for that. I’m not sure you really need one. I’ll just give you my permission.” We told him that it would be better for our organization, the Secret Service and his office if everything was in writing.

I began to list information usually contained in a permit – name of group, time, place, purpose, and he interrupted me, saying, “You seem to know what you need. Come back here.” He pointed through a doorway to a back room. “Just sit down at that typewriter on the desk. Write your permit, and I’ll sign it.”

So I sat down in front of the manual typewriter on the cluttered desk and, with Courtney’s assistance, composed the permit that would authorize our use of the park and could be presented to the Secret Service agents outside the Carter home if they asked for it. Mayor Banton read it and signed it just as I had typed it.

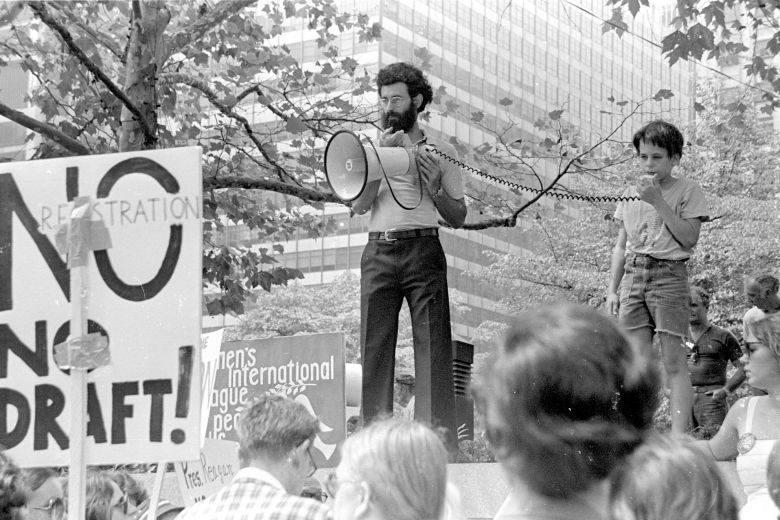

More than sixty members of Friends meetings throughout the Southeast and beyond indicated that they would participate in the all-day vigil (10 a.m. to 8 p.m.). On Friday night, December 17, we conducted two orientation sessions for the arriving participants, one at the Atlanta Friends Meeting and another at a motel in Americus, near Plains. I had compiled a background packet, briefing participants on the issues we wanted to address and the logistics of the vigil. Participants were divided into three groups. Everyone was to be on the vigil line for the first and last hour. In between was a rotation schedule that kept two groups vigiling while one group rested. Some participants chose to vigil the entire ten hours.

We began with singing and then took up the silence. In the late afternoon, President-elect Carter walked over to greet us and went down the line shaking each person’s hand. We presented him with the list of issues we wanted him to address early in his administration. He thanked us and said that he appreciated us bringing our concerns to him.

As it grew dark, we lit candles. Soon we saw a lone woman, not accompanied by Secret Service, cross the corner from the Carter home. The President-elect’s mother, Lillian, approached the vigil line. I was holding a box of candles. She said, “Boy, give me one of those candles. I hate war.” She joined the vigil for the last hour. We concluded in song, “Blest Be the Tie that Binds.”

On January 21, 1977, the second day of his presidency, Jimmy Carter fulfilled his promise, pardoning Vietnam-era draft resisters (though he did not extend the pardon to military war resisters). In June he cancelled the B-1 bomber program. In July the U.S. voted in favor of a UN Security Council resolution recommending that the UN General Assembly admit Vietnam as a full member. (It was not until February of 1994 that President Clinton finally lifted U.S. trade restrictions on Vietnam, and in July 1995, twenty years after the war ended, relations between the U.S. and Vietnam were normalized).

If I were asked to assess the impact of the vigil on President Carter’s decisions, I would say “partial.” The policy changes listed above were only part of what we were urging on the new president, and our vigil was only a small part of the efforts to cancel the B-1 bomber and heal the wounds of the Vietnam War. In February of 1977, more than 165 demonstrations had been held across the country on the same day, urging Carter to hold fast to his commitment to cancel the B-1. Decades of further effort by many people were required to normalize diplomatic and trade relations with Vietnam. The U.S. promise of reparations for the damage the war did remain only partially fulfilled forty years later.

Our vigil did convey “a spirit of support and shared hope.” And President Carter and his mother appeared to trust that spirit. We can only conjecture on if and how the trust he felt for us may have played a role in the decisions he made or decided not to make.

And then there is Mayor Banton and his successors. I’m sure in the years that followed, as people descended on Plains to conduct public events for their causes, the mayor knew how to write a permit. Perhaps there was even a form modeled on the one Courtney and I composed. And, today, the town of Plains does have an office at the County Courthouse – no more “backroom deals.”