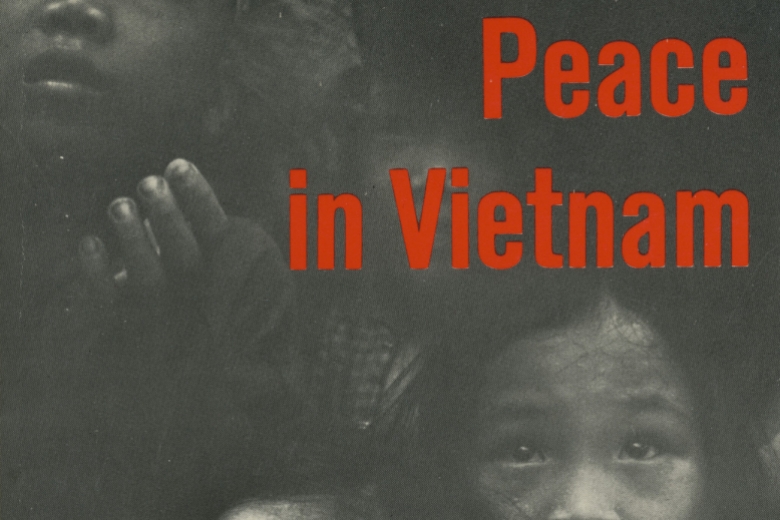

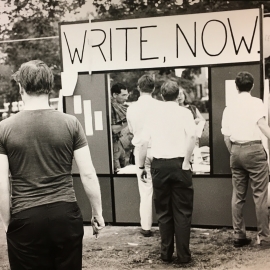

From 1965-70, AFSC helped build the antiwar coalitions that challenged U.S policy in Vietnam. Bridging the divide between liberal faith groups and more radical antiwar resisters, we argued for a big tent and broad peace movement. Through our research and communication project NARMIC (National Action/Research on the Military Industrial Complex), we provided critical facts and analysis to help activists confront corporate war profiteers. For years, AFSC and Quakers were also at the center of the draft resistance movement.

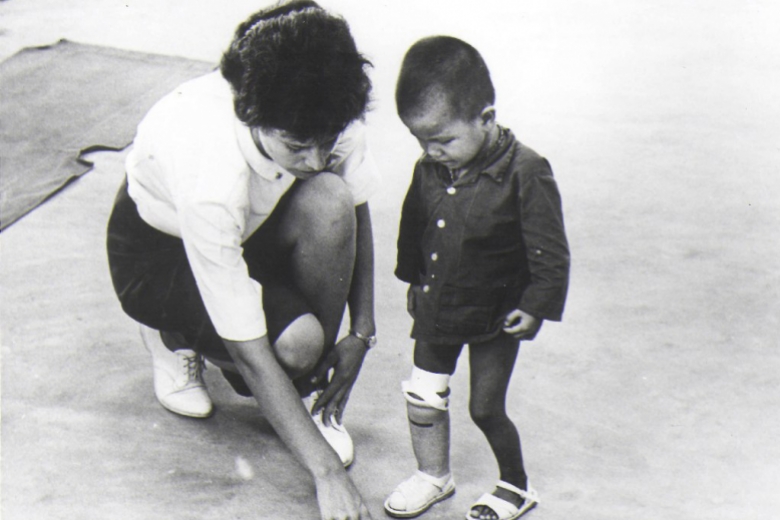

After President Nixon announced the “end of war” in 1973, NARMIC and our staff on the ground in Vietnam revealed another story. Automated weapons were continuing to rain terror from the skies, not only in Vietnam, but also in Cambodia and Laos. From 1973-75, we campaigned and convened stakeholders to help bring a real end to hostilities. By 1978, when few nongovernmental organizations were permitted to remain in the region, AFSC continued to work for peace and reconciliation, having earned trust on all sides.