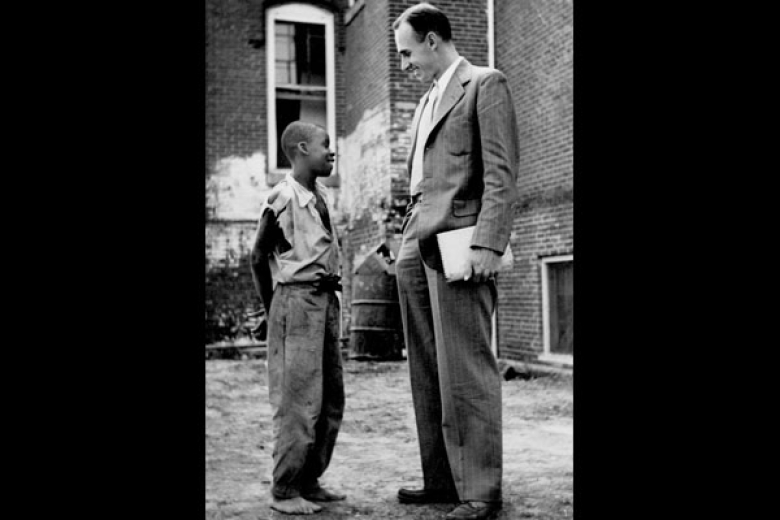

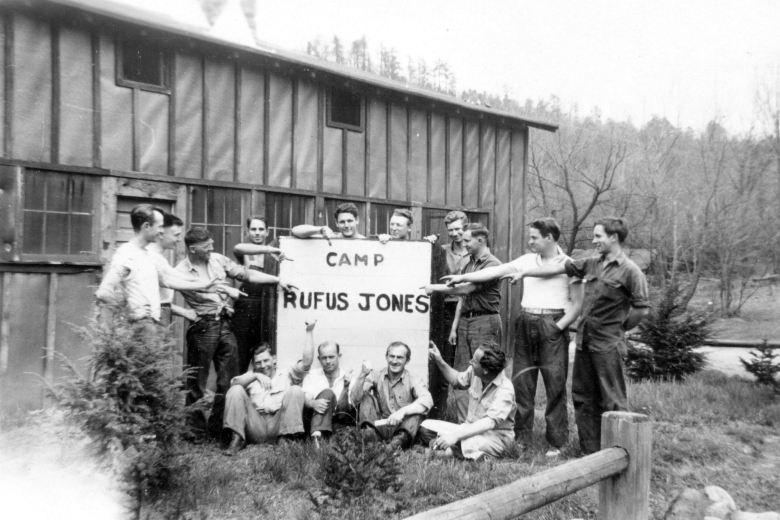

Congress created the Civilian Public Service in 1940 so that men opposed to combat could offer meaningful alternative service to their nation at war. The three historic peace churches (Quaker, Brethren, and Mennonite) partnered with the Selective Service to administer the organization. About 12,000 men participated, along with a significant number of women who volunteered.

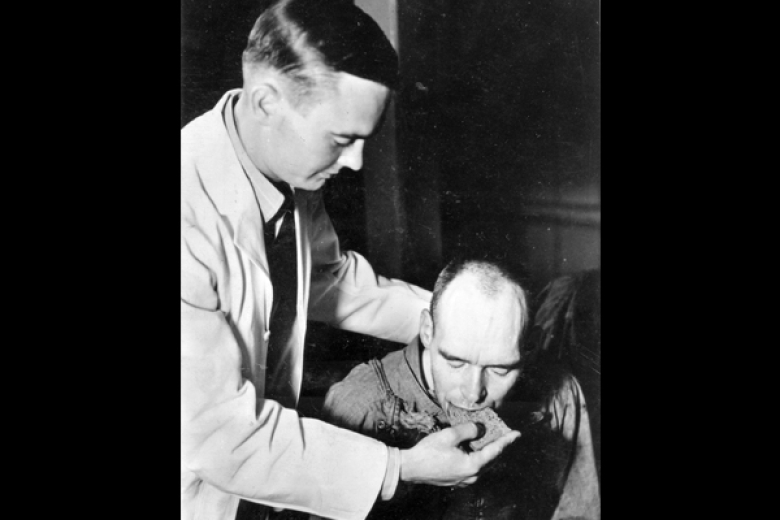

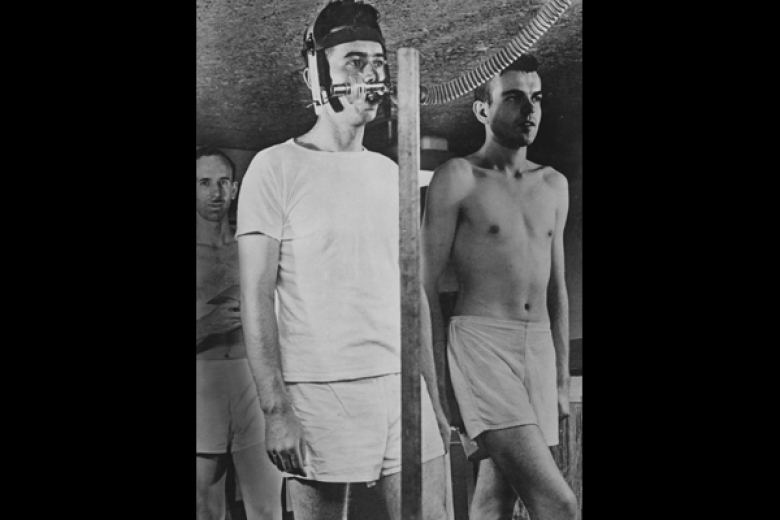

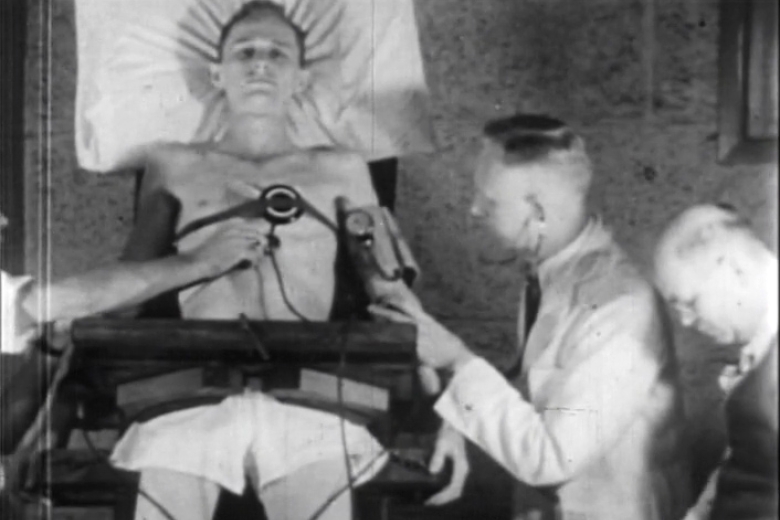

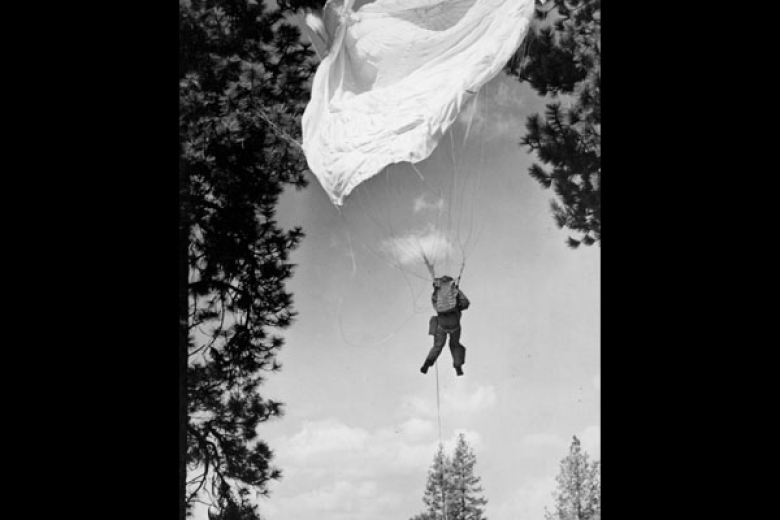

Over time, CPS assignments ranged widely, as did the education and politics of the men serving. Some felt the need to sacrifice so keenly that they agreed to serve as human guinea pigs. They were subjected to disease, deprived of food and water, and exposed to hostile environments—all in the name of protecting their country nonviolently.

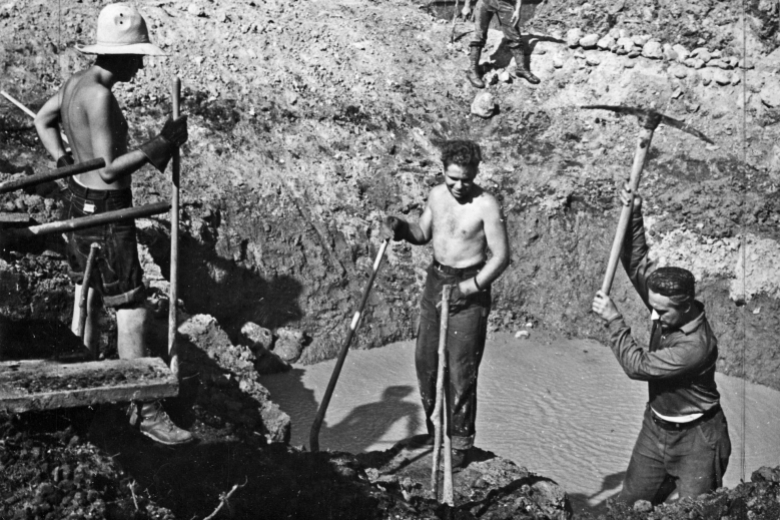

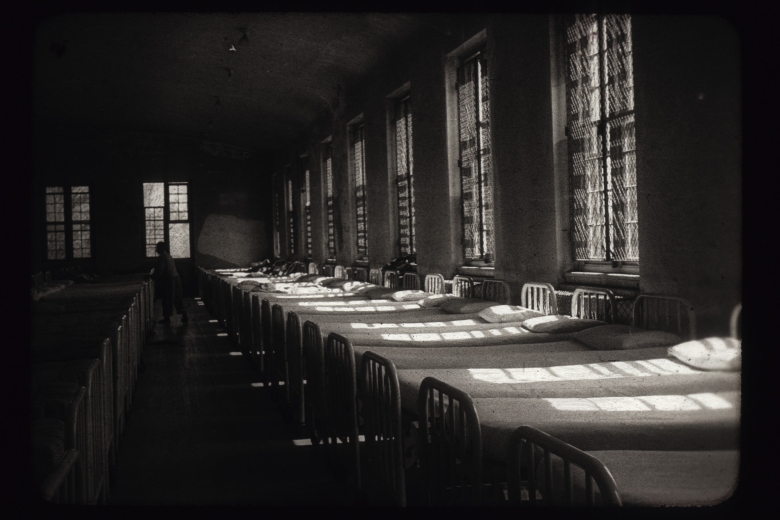

Many other CPS workers simply spent long days at tedious jobs in rustic, remote camps. Approximately 2,000 worked in mental hospitals, or training schools for people with disabilities. Horrified by the conditions they found, the men and women of the CPS fought to change this status quo—both during and after the war—and they succeeded. Many Quaker leaders in education, service and peace building began their careers in Civilian Public Service.