When I enrolled in the Navy Y-12 program in May of 1943, it was my understanding that after a brief training we would be commissioned and sent out to fight. However, after getting uniforms, starting military drills, and going to classes, it soon became evident that the Navy planned for us to complete eight semesters of engineering training.

I was appalled. It seemed certain the war would be over by then and I would have missed it. I was determined to fight for what I thought then to be a glorious cause. I was not wrong. By the time I finished school, WWII was over.

I became a teacher at Blackburn College in south Illinois. John Forbes, a Quaker, was a history teacher at Blackburn. He ran a Quaker fellowship which I joined – it was inspiring. A traveling AFSC representative joined us for one of those fellowships to talk about AFSC work camps and that became a turning point for me. The year was 1950.

At about the same time as I heard about AFSC work camps, another traveling visitor told me of a lake hotel in Michigan looking for a buyer. I was excited because I was looking for a good way to spend summers while teaching. I visited the lake and saw the two-story hotel. I saw possibilities of hiring students to staff the hotel.

On returning to college I mailed a check of $1,000, my total savings, as a deposit on the $30,000 price. As soon as the check was mailed I began to have second thoughts. After all, I had also been interested in going to the AFSC work camp for the summer. Did I really want to give that up for the hotel and its promise of riches?

The next day I called the hotel owners and they accepted my change of heart. Instead, I went to work camp and subsequently got involved in other Quaker activities, which moved me from teaching to community activism. What a different path – what if I had gone through with the hotel and stayed at Blackburn with summers at the lake for the rest of my life?

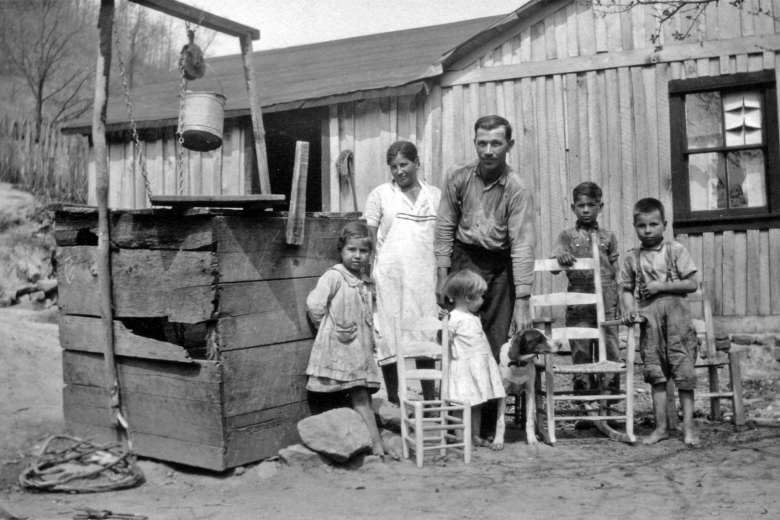

Instead, I set out for SW Harbor on Mt. Desert Island in Maine for a whole new adventure. The work camp was designed to work with the poor cannery workers and their families. The plan was to set up a day camp to which cannery kids and town kids would come in order to bring the two communities together. We ran the day camp and I chose to work with the older kids, drawing upon boy scout experiences for ideas, but we were not as successful as we wanted to be in recruiting participants.

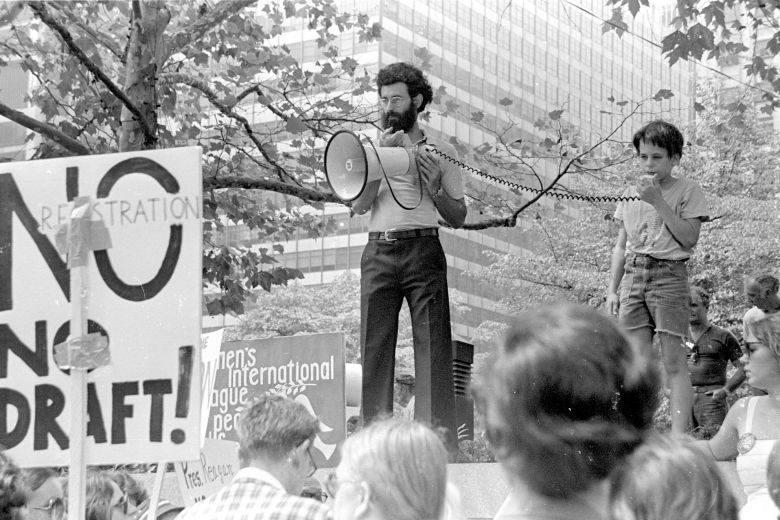

Meanwhile, as camp started, the Korean War was getting started too, and that served to stimulate a lot of discussions. There were several strong pacifists among the group and I argued fiercely with them at great length, but when all was done I became convince that I could not fight in such a war.

Thus I had a dilemma. Having come to a position of conscientious objection to war; I wrote a letter of resignation to the 2nd Naval District of the US Navy. Upon refusal, due to the active state of war, I appealed to the Secretary of the Navy. Upon his refusal, I appeal to President Truman. Upon his refusal I was frustrated and dejected.

It was in this state that I hosted a visiting speaker at Blackburn – Reverend Graebel. I told him of my predicament and he said that although he didn’t agree with the C.O. position, he did agree with my right to hold such a position and that he would talk to “Harry” (the President!). I thought this was the voice of an overactive ego but six weeks later the phone rang and a he said, “Congratulations, you’re out.” The Reverend had arranged for my resignation to be accepted. So much for my estimation of the good Reverend!!

After being released from the Naval Reserve I was subject to the draft. My draft board notified me that they had classified me as IA, extremely draftable. I appealed the classification and my AFSC advisor suggested that I look at my file at the draft board, my legal right. I was appalled – the VP at my high school, for example, said that I was a coward because I didn’t play varsity sports. I rebutted this and many other negatives at the appeal hearing by the draft board. Their greatest problem was that I had been protected from WWII by the Navy Y12 program and now it was time to pay my country back for their investment. I understood, but one’s conscience acts on its own time. I did point out that I was prepared to do alternative service.

In the end the country drafted me four days too late. I was reported for induction in to the Army with six days’ notice but law called for 10 days’ notice. With help from my AFSC councilor I was finally classified above age for the draft because I turned 26 before the end of the 10 days.

I was liberated to proceed with AFSC as my own personal alternative service. I made plans to go to work camp in Mexico, and then Finland, and finally in Maine. I did service for three full years (1951-1954).