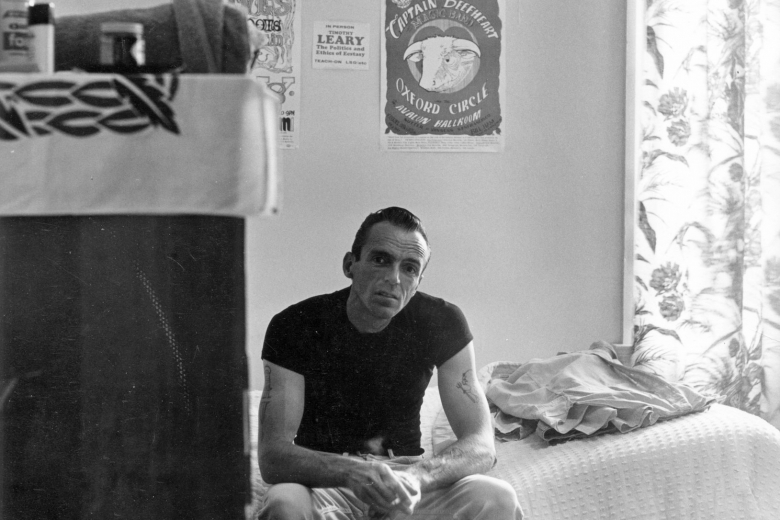

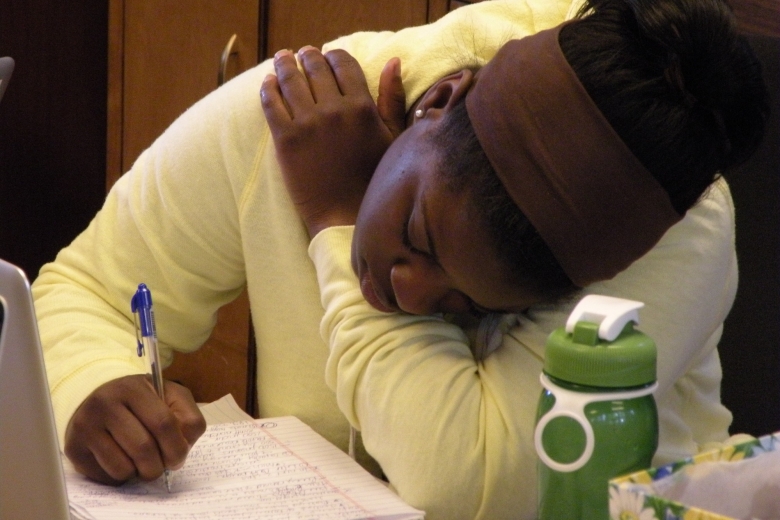

When harm is done, the Quaker way is to seek healing and reconciliation, not retribution. This approach has guided AFSC’s “healing justice” work since its inception. In the 1960s we began urging Friends Meetings nationwide to visit and assist people in local prisons. In halfway houses and pre-trial programs, our staff saw firsthand how the justice system mistreated communities of color and those at the margins of society.

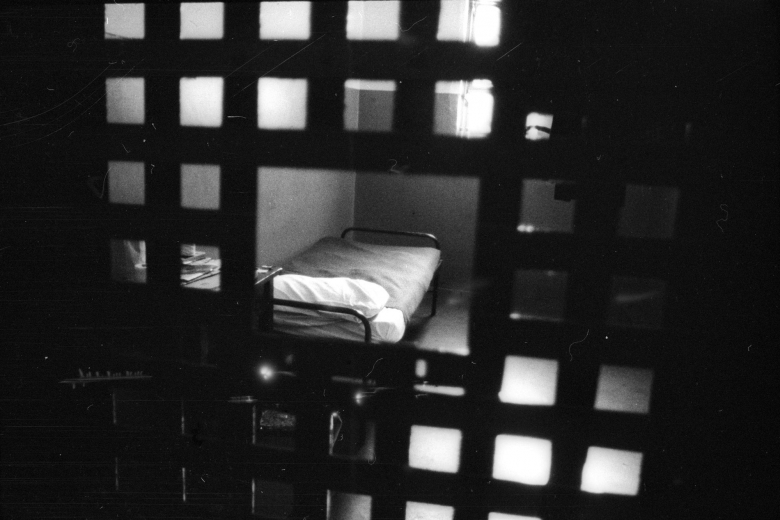

When the police killed dozens of people during urban uprisings in 1967, AFSC took a stand against police brutality. Our publication “Struggle for Justice” exposed racial bias in sentencing and recommended reforms. As “tough-on-crime” laws of the 1980s swelled prison populations, AFSC worked to support those affected—both in prison and in the community. We rallied faith groups to resist the death penalty and to oppose solitary confinement. Today, ending mass incarceration and for-profit prisons are at the center of our agenda.