Written by Mark Miller

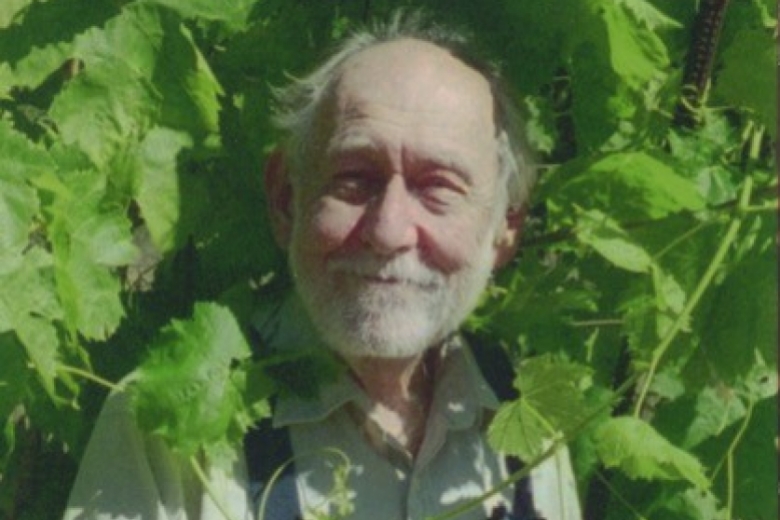

As I write this, Wes Huss, at 98 years, is about as long-lived as the American Friends Service Committee. I met Wes in May 1989, when I joined the staff of AFSC as the Community Resources Secretary for the Pacific Mountain Region. He was about 70 then, physically and emotionally at ease, lean, long-limbed, and sporting a trimmed white beard. He was the director of the Region’s American Indian Program. We shared the same workspace in the Regional office, then a re-purposed, large, old home on Lake Street in San Francisco. He almost immediately became my most valued mentor and source of support. Wes was an ideal teacher — intelligent, articulate, forthright but soft spoken, a keen observer, and a deep listener.

His most important advice about overseeing Community Resources programs was that my primary role was not to supervise program directors. It was to listen to and support their leadings and the leadings of the communities that they represented and served. It was not to direct their efforts. It was, if possible, to help secure the resources and platform they needed to successfully operate their programs. Of course, in trying to assume the role he described, I experienced the inevitable and honest tensions that arise when trying to respond to the leadings of AFSC leadership, committees, and funders while following the leadings of the communities with whom we were allied. I learned quickly that Wes was a consummate guide in managing these tensions.

Over time, Wes related bits and pieces about his own background and life work. He never presented this systematically. His ease was that of someone who needed little or no self-promotion. As I began writing this, I explored whatever information I could find that would enable me to understand more about what Wes told me so long ago. I discovered that the personal qualities, values, and energy he brought to his work must have appeared early in his life because they were manifest in the earliest parts of his life’s work.

Approximately between the ages of 24 and 27, as a conscientious objector (CO) during the Second World War, Wes served the AFSC as a director of the AFSC-operated Civilian Public Service camp near Coleville, California — Camp 37. The camp was in the high Sierra, south of Lake Tahoe near the Nevada line. It was one of well over 100 camps into which conscientious objectors were drafted to perform public service without pay. Camp 37, as were many others, was established to provide the U.S. Forest Service with firefighters when manpower was in short supply. There, Wes faced the immediate and inevitable tensions that arose among the American Friends Service Committee, the Selective Service, the Forest Service, and the strong-minded, strongly-principled, and righteously rebellious COs themselves.

Robert Kreider described the governance of the CPS: “A three-layered administrative structure [within the Civilian Public Service] appeared: 1. Selective Service, an agency which came under the direction of army officers; 2. the National Service Board for Religious Objectors (NSBRO), a majority of the members from the Peace Churches; 3. church operating agencies, principally the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), Brethren Service Committee (BSC) and Mennonite Central Committee (MCC). Although the lines of authority were at times blurred, Deputy Director Colonel Kosch spoke for Selective Service: ‘The draft is under United States government operation. Conscientious objectors are draftees as soldiers are. Their activities are responsible to the government. The Peace Churches are only camp managers.’ This uneasy church-state partnership, with its strains and flaws, survived for seven years.”

Among the Camp 37 newsletters written by camp CO’s, I found their list of camp residents. Adjacent to many on the list were cartoon depictions of each. Next to “Wesley Huss,” the cartoonist had drawn a trained seal, balanced on a small platform and balancing a large beach ball on the tip of his nose. I am confident that Wes chose this image. It illustrates his efforts to balance the conflicting challenges he faced and his self-effacing nature.

But the most important thing I observed about the Camp 37 newsletters is their unfettered and often humorous content about camp events and governance, work, philosophy, religion, art, and resistance that included, for example, reports on CO resistance around the country. The room for freedom of expression, humor, cartoons, and fearless discussion of CO concerns and resistance that I found in the newsletters reflected the best of what AFSC—and Wes Huss—could provide.

Further evidence of the nature of Wes’s role was provided in a passage of Basil King’s Learning to Draw/a History. In it, he recalled a meeting [apparently in the 50’s or 60’s] with an art student named John, who, during a counseling session with King, noted that King had gone to Black Mountain College. ”John asked, ‘Then you must know Wes Huss.’ ‘Yes, he taught theatre,’ and before I could say more he looked at me and began to cry.”

“He said that he had been a conscientious objector in the Second World War and had been sent to a camp… He said Wes held them together. Wes had them write plays, do pantomime, keep their bodies active.”

Indeed, Wes did become a respected theater teacher at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, which, from the late 30’s up to 1956, attracted students and faculty that included some of the foremost artistic, radical, and creative minds of the 20th century. It was a haven for progressive, art-based, education as conceived by John Dewey. Wes taught there during the first half of the 1950s. Wes’s notion of theater was paraphrased by one student as “…artifice, that the audience was an active co-operator, that performance began in the imagination, and entered a dancing give and take with the situation at hand at that moment.” By the time Wes joined the college, it was struggling to survive in a hostile national environment and the students and faculty had become, as Wes said, “a community of subsistence dwellers.” During this difficult time, Wes also functioned as the college treasurer and business manager, stretching its meager resources while conceiving and leading repeated funding efforts to keep the college alive as long as possible. He brought the facility and determination required to manage scarce resources that he developed at Black Mountain back to AFSC not long after.

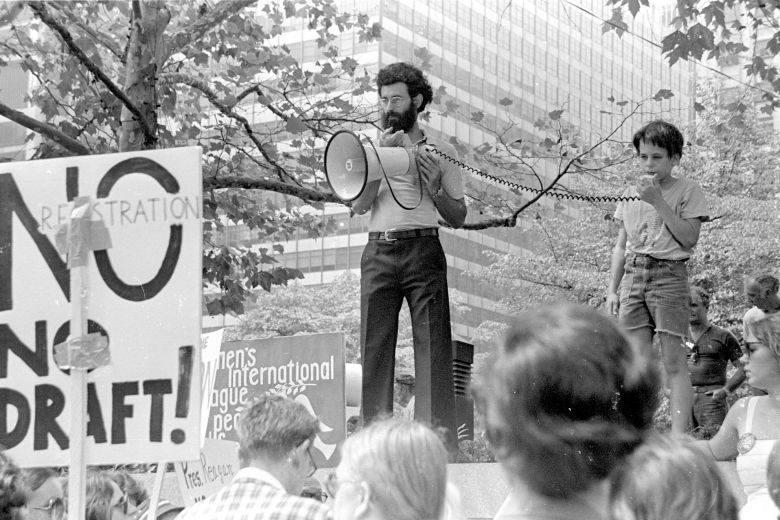

Wes once told me that during his time at Black Mountain, he became involved with the history and current lives of the Cherokee who remained in that area. I don’t know and could not find more about that involvement, but I do recall him telling me that his time with the Cherokee led him to ultimately join AFSC’s American Indian work in 1957, where, well up into the 1990s, he significantly bolstered AFSC efforts to support American Indian leaders as they addressed matters of concern to them. Wes provided critical, decades-long assistance to the efforts of American Indians in the Bay Area as they organized and institutionalized the Intertribal Friendship House in Oakland to provide a cultural center and gathering place for American Indians displaced or migrating from reservations. The Intertribal Friendship House continues that mission in 2017. In addition, he augmented and provided leadership to AFSC staff and committee members who were supporting an array of American Indian struggles that included maintaining and defending tribal sovereignty, securing federal recognition of existing but previously unrecognized tribes, the difficult but successful organizing by American Indian prisoners for the establishment of religious equity in California prisons, exposing and opposing programs that removed American Indian children from their homes and culture to put them in boarding schools or up for adoption, reinforcing traditional ties between American Indian elders and youth, protecting sacred places, and strengthening the American Indian Movement.

During my 12 years on the AFSC staff, I observed, learned, and tried to apply the proven approaches to social justice work that Wes embodied and championed. I fervently hope that AFSC will always also champion those approaches. Foremost among them is the primary commitment to support and strengthen communities and community leaders struggling for social justice. This means rendering assistance requested and guided by those communities and strengthening, rather than supplanting, their leadership. A corollary of this that AFSC should employ staff from the communities it serves and understand that staff and the programs they direct are first and foremost a part of and accountable to those communities. In short, it is to follow the guidance that Wes offered me in 1989.

As I write this final exhortation, I am filled with memories of my work with AFSC staff who have truly represented and served their respective communities. My time working with Wes and those program directors is one of the greatest privileges of my life. I think of farmworker leaders Pablo Espinoza, Graciela Martinez, and Luis Magaña, I think of the former prisoner and American Indian spiritual Ieader, Isidro Gali. I think of the human bridge between Indian elders and youth, Vic Yellow Hawk White. I think of the 20 years of popular education and cultural work sustained by the Central Valley immigrant leader, Myrna Martinez Nateras. May AFSC always rely on and employ the leadership of community leaders like these and those who, like Wes Huss, honor and support them.