“You people are about to commence upon what I like to call ‘The greatest adventure of the century.’” One couldn’t help feeling a prickly feeling down the spine and a slight quickening of the heart at the words of challenge uttered by Herberto Stein, a Quaker statesman at the UN and a Mexican, as he described the work in which we were about to engage. We were 40 young men and women working in Quaker work camps in Mexico. We were about to scatter in smaller groups to live and work in rural villages. We were incredibly excited.

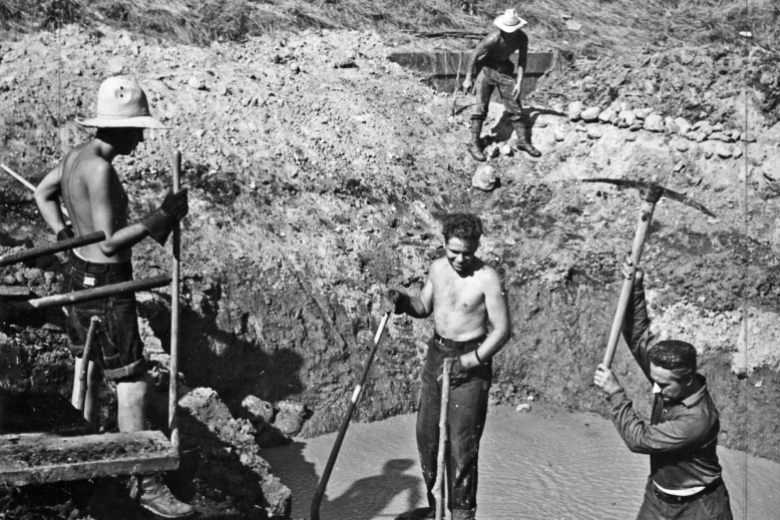

My particular town was Jalacingo in the mountains of Vera Cruz in eastern Mexico. Three blocks in any direction and one was out in the country. Typical jobs included laying new sidewalks to provide a sanitary place for barefooted townspeople to walk, repairing the sewage system, preparing a medical clinic for use etc. Sometimes we wondered if this casual and monotonous work was truly the ‘adventure’ for which we had been primed. Often we felt we were not truly helping to lift the desperate poverty. But, in our deep and searching discussions as a group, we came to understand how it is often necessary to work patiently to gain acceptance and lay groundwork of interest and confidence. We were the catalyst which brought middle class Mexicans to examine these problems in their own neighborhoods.

Certainly one of the outstanding values of the experience was its contribution to our own education. Perspective and insight into other cultures and backgrounds can serve to dissolve the prejudices and stereotypes that have too long served as barriers to international understanding and goodwill. In this retrospect, our group in Jalacingo was remarkably successful.

In the spring of 1953 when I had returned from my Mexico work camps and was waiting to go to a Finland work camp, I visited AFSC in Boston. George Bliss asked me if I would like to be AFSC’s representative to the Maine Indians. So, upon returning from Europe in November of 1953, I joined the New England office staff as the Indian Agent. I divided my time between fundraising and visiting Indian groups.

In a situation typical of European colonies, the tribe had become divided into a Catholic and a Protestant group and they cooperated on nothing. As an amateur community organizer, I was at a loss as to how to deal with the situation. Some told me that what was needed was recreation for the kids, others toyed with plans for marketing baskets, others spoke of money Maine owed them, some wanted to run their own lumber business as a tribal corporation.

Loneliness, failure as a fundraiser, and lack of confidence as a community organizer combined to cause me to go back to Boston in September of 1954 to attend the Boston University School for Social Work and learn more about community organizing. I became a social worker because my experiences with AFSC showed me both my weaknesses, but also my strengths and a path forward.