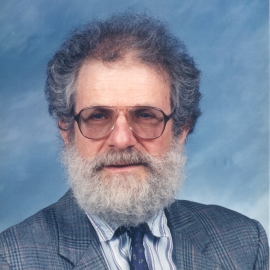

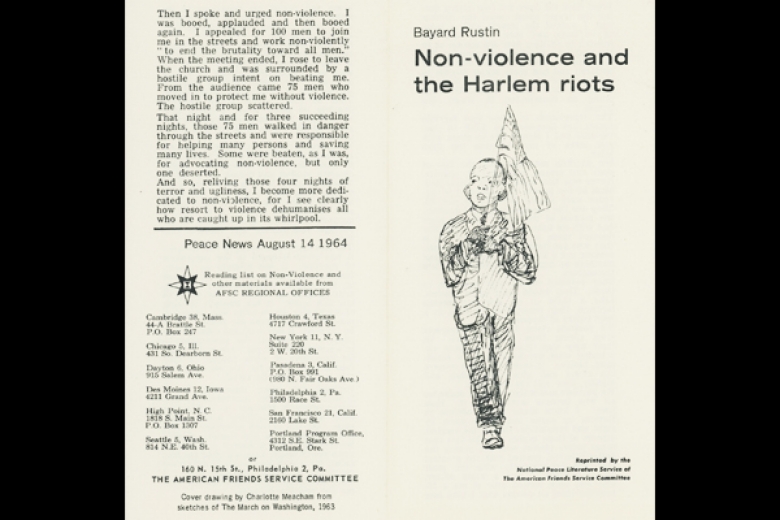

In the 1920s, AFSC hired Crystal Bird, a young African American woman, to travel the country and speak about “the problems, needs, and culture of the colored race.” This first effort to bridge the racial divide was followed by decades of work to combat lynching, expand employment and housing opportunities, and integrate public schools. Impressed by the nonviolent civil rights leadership of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., AFSC became one of his early supporters. We published 50,000 copies of King’s “Letter from Birmingham City Jail,” which confronted the failure of faith groups to stand up for racial equality.

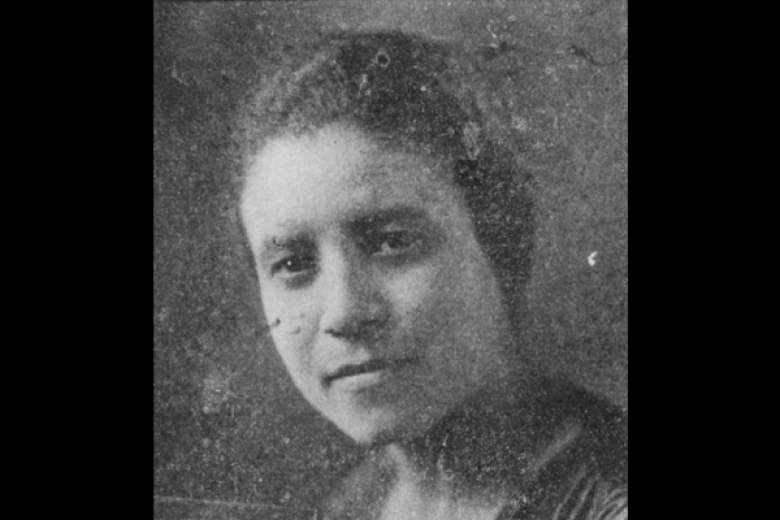

Following the 1954 Supreme Court decision ordering desegregation of public schools, our Southern Program helped Black families enroll their children in formerly white schools. In Prince Edward County, Virginia, where the school board closed their schools rather than integrate, we placed dozens of Black high school students in northern schools. AFSC also played a prominent role in the Poor People’s Campaign of 1968, raising issues of economic and racial equality.

Today, our commitment to racial justice continues as we examine structural racism within our own organization and support a new generation of activists confronting racism in our culture.

![According to Steve Cary, “King and the civil rights movement played a big role in the AFSC’s evolving understanding of nonviolence. …[our] stand against violence expanded to include the roots of violence—injustice, poverty, and oppression.” Man speaks into a microphone held by a reporter, filmed by other staff.](https://peaceworks.afsc.org/sites/default/files/styles/full/public/images/civil11.jpg?itok=TEBZXwps&c=1de6f8b7942177485abbd418ae0e335b)